Lately I have found myself questioning questions. They are indeed the heart and soul of inquiry. Questions give voice to our passions and our curiosity. When we bravely release a question into the air – we are vulnerable, open and ready to learn. Where once, question-asking was the teacher’s territory, in an inquiry classroom, students’ questions are as important - if not more-so than the teacher’s. The presence of students’ questions (orally and visually) in a learning space is one of the first signs that I have entered a zone of inquiry. Many of the sessions I have recently facilitated with students have focused on the art of question-asking. I regularly hear teachers voice their frustration with what I think of as ‘sham questions’ – those designed to teacher-please or simply to fulfil a requirement - frustratingly narrow, irrelevant or poorly constructed or students who ask no questions at all. Part of the problem can be that we have failed to move beyond the linear notion of inquiry that framed our previous thinking (“What do you know? What do you want to know....?”) and to embrace a more invitational, organic and cyclical approach. In short, we need to move on from the KWL chart.

A couple of weeks ago, I worked with a lovely group of year 6 students who had been busily drafting questions for personal inquiries following their shared inquiry into Australia’s connection with Asia. While the interest was high, this was no easy task for many of the students. We soon realised that some kind of “success criteria” were needed to help them figure out what would constitute an effective question for this particular kind of task.

Drafting some initial criteria for questions

Drafting some initial criteria for questions

We spent the best part of an hour exploring the question “What makes a good question?” Of course – the answer is “It depends”. We need to be clear about the purposes and nature of the task. Through conversations, trial and error, design and feedback - we eventually devised some success criteria to guide the formulation, self and peer assessment of their questions. Even with the criteria available, however, some students still struggled to articulate their interests beyond a general sense that they ‘wanted to learn more about….’ It reminded me how often I am in this exact same position with my own learning. And even when I think I know what I am looking for – what I end up finding out prompts me to re-think my original intent. Whether or not I begin with a question depends on the nature of my investigation. I mostly end up asking something…but certainly not always from the outset. I read this recently and it really struck a chord:

- “The best way to find out things, if you come to think of it, is not to ask questions at all. If you fire off a question, it is like firing off a gun; bang it goes, and everything takes flight and runs for shelter. But if you sit quite still and pretend not to be looking, all the little facts will come and peck round your feet, situations will venture forth from thickets and intentions will creep out and sun themselves on a stone; and if you are very patient, you will see and understand a great deal more than a man with a gun.” Elsbeth Huxley 1959: 272 *

Developing the capacity to ask questions remains a significant part of the inquiry teacher’s role BUT to make this work we need to attend to two things. Firstly (and somewhat ironically) we need to acknowledge that inquiry does not need to begin with a question…they can pop up along the way or even at the end of a process of investigation. Secondly, we can spend time exploring the art of questioning itself. We need to inquire INTO questions - empowering students to frame and reframe questions as needed. Here are a few tips that may help you move beyond the tyranny of the KWL chart

• Invite rather than insist on questions early on in an inquiry journey.

• Try using the term ‘wondering’ rather than ‘question’. Wondering’ has a softness to it that invites risk taking.

• Encourage/display/celebrate questions about all sorts of things – not just those things associated with a “unit of inquiry”.

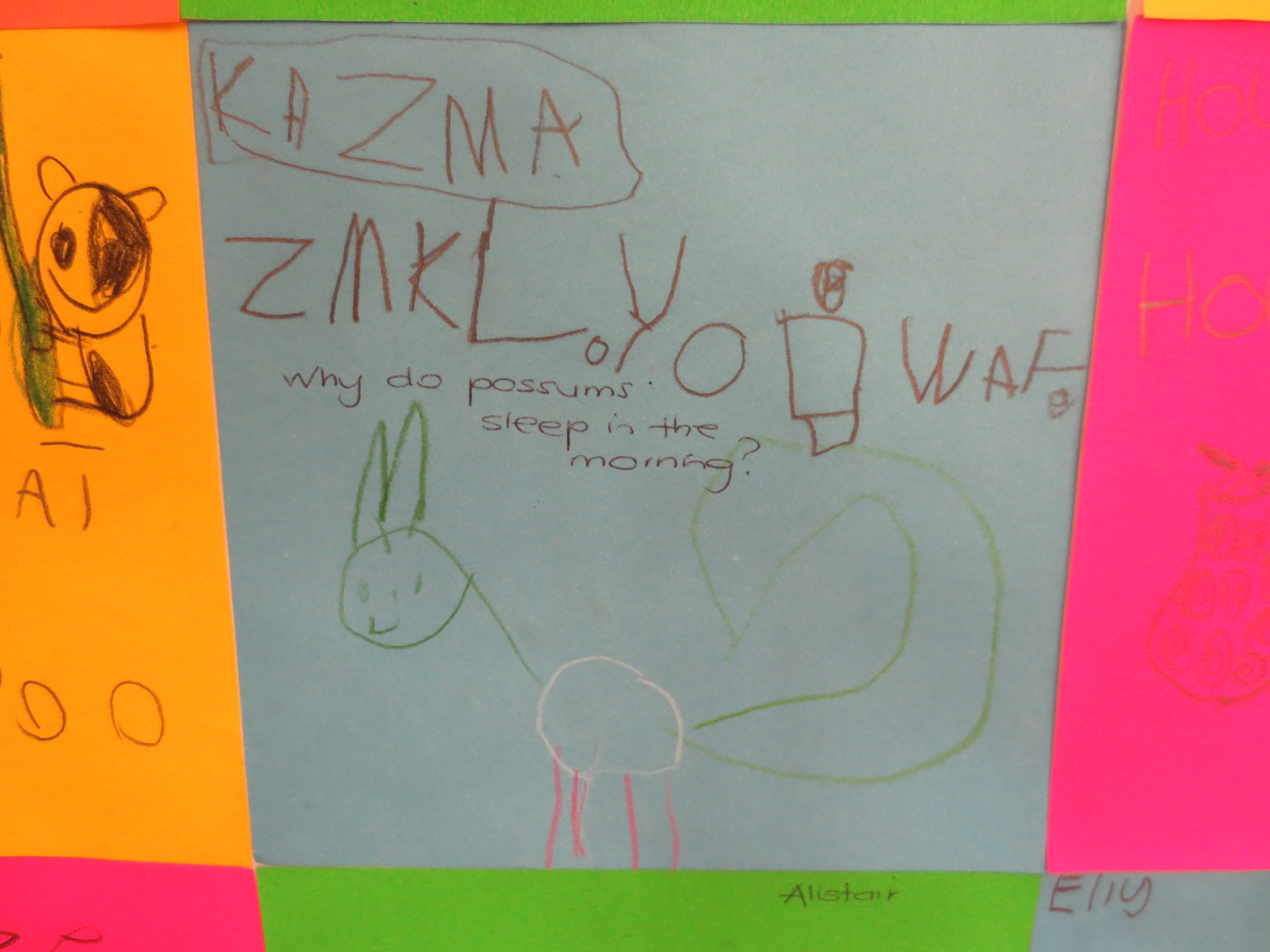

“Why do possums sleep in the morning?” a five year old’s personal wondering

• If you are using something like a ‘wonderwall’ help students see it as a work in progress – a dynamic space that allows for questions to be taken down, added to, refined and grouped throughout the journey

• Share YOUR questions – model curiosity and the art of framing questions by actively and authentically participating in the process yourself!

• Allow students time to play with the material about the area under investigation. Contradictory as it sounds, we often need to do some finding out before we know what we want or need to find out! Use provocations to stimulate questions.

• Avoid demonising the ‘skinny’ or closed question. Most researchers need to use a combination of both to guide their investigations. Help students notice the way different kinds of questions are needed for different purposes.

• Challenge students to find a question as a result of their investigation – a question can be a conclusion!

• Recognise that the impetus for investigation may come more from a desire to make/build/design/create. These generate questions but often through the process.

• Devise compelling questions to drive rich inquiry (I have blogged about this previously: http://justwonderingblog.com/2012/10/28/walking-the-world-with-questions-in-our-heads/)

• Finally, spend time inquiring into questions themselves. They are fascinating linguistic expressions! Play with questions – when students DO generate them, examine the different ways they are structured. Ask students to group them in different ways. Some of the challenges I have given students recently include:

Which questions do you think will be the easiest for us to answer?

Which will be the hardest? (Why?)

Which questions are you most excited/least excited about?

Which ones are open/closed?

Let’s group them according to best ways to find out about them? Which are google-able? Which are not?

Most-least important?

How flexible are we about our students’ questions? How much time to we spend reflecting with students on the nature of questions themselves? Can powerful inquiry happen if we DON’T ask questions?

Just wondering….

* Huxley, E (1959) The Flame Trees of Thika: Memories of an African Childhood Penguin