One of the most significant changes in our practice as teachers in recent years has been a move towards greater transparency in relation to our objectives. Once, what we wanted students to learn was ‘secret teachers’ business’ , now we are much more aware of the power of sharing our intentions. One of the most popular vehicles for sharing learning intentions is through the use of “WALTs” (‘We Are Learning To) statements. The full blown version of this approach includes TIB (This Is Because) and WILF (What I am Looking For). A colleague in New Zealand wryly observed to me the other day that she felt kids were in danger of ‘death by a thousand intentions’ as she noticed the explosion of WALTS crowding the classroom walls. I’ve never been a huge fan of WiLF , in particular . The suggestion that I am the one looking for the learning rather than the students themselves has never sat right with me - although I played with it for a while. More recently, I have been feeling similarly uneasy about the subtext of the phrase “We are Learning To”. Announcing what we will be learning to do/understand is uncomfortably declarative and certain whereas inquiry treats learning as more complex and emergent.

Don’t get me wrong, I am all for sharing learning intentions. I like the word ‘intention’ as it signals a general desire or expectation but falls short of being an absolute. Our intentions help us set the scene, give us direction and sets us on a path. In an inquiring classroom, teachers are highly intentional - they are guided by clear principles, they avoid time wasting activities and are driven by a powerful sense of real purpose.

But I’m re-thinking my even sparing use of ‘WALTS'. When we announce to students what they WILL be learning – are we not, even subtly, reigning in the potential for discovery? If inquiry teaching is about giving students agency and helping them construct and create understanding - then I think need to be cautious about such declarations.

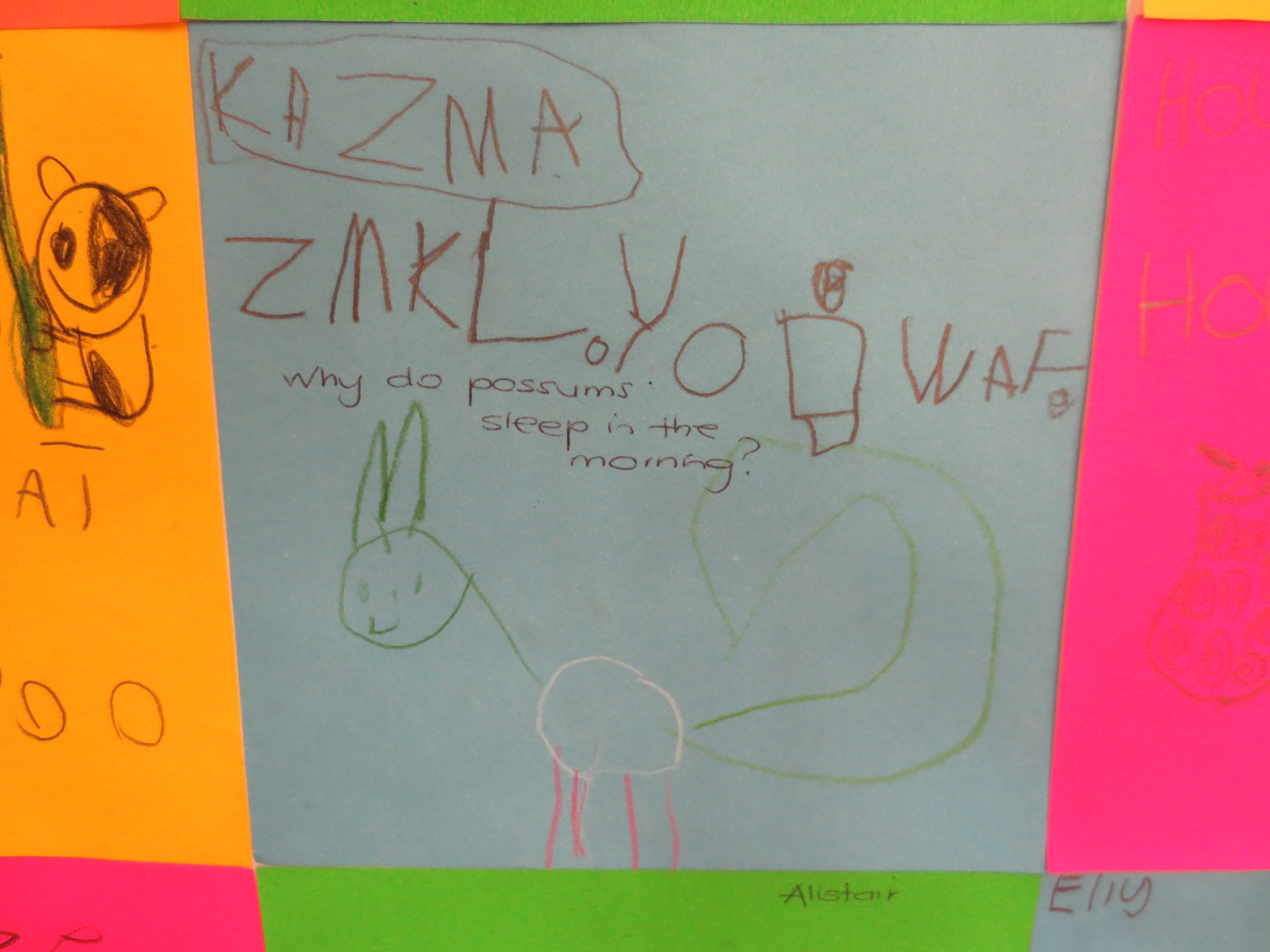

A practice that sits much better with my inquiry principles is to share intentions in the form of questions rather than statements. I want our learning experiences to remain intentional and transparent – but it feels better when I articulate this in question form. For example, I might once have said to students that, as self managers, they would be “learning to devise an effective action plan to meet a goal”. Now, I pose a question: “How can we devise effective action plans to help us meet our goals?” As with ‘WALTS’ these intentions-as-questions may be lesson-long or may run through the course of an inquiry.

When I pose this question, I immediately invite my students to be researchers. As they go about the task of designing and working with their action plans, we all try to notice what we are learning about the process. If an intention is framed as a question, we naturally gather data, share and reflect. We can create dot points that easily become success criteria. And it’s not about getting the right answer (ie - the teacher creates a kind of ‘sham’ question with pre conceived answers) - when we set intentions as questions, there is more room for discovery, for the unexpected and for debate between students and that makes for a much more satisfying learning experience all round.

Clarifying our intentions through questions does not have to be teacher-led. Why not ask students what THEY think the question/s might be that drive a particular learning experience?: “What questions might we carry into this?” “What might this help us learn more about?” Establishing intentions as a conversation between teachers and learners again sees a better ‘fit’ with the core principles of the inquiry classroom.

Generic skills and dispositions within the areas of thinking, communicating, researching, self managing and collaborating provide fertile ground for intentions-as-questions. Here are some examples:

How can we record our observations accurately?

What roles can help a team function smoothly?

How can we show someone we are really listening?

What strategies help us manage our time more effectively?

What helps me stay more focused on a task?

How can we edit our own writing more effectively?

How can we determine the most relevant parts of a text?

How can props be used to power up a presentation?

How can we use creative thinking to help us problem solve?

How can we give each other useful feedback when working in a team?

What are some efficient methods to take notes when viewing clips for information?

The examples here still express a learning intention - but they invite the learner to investigate and construct their own ideas in response.

The tension between what we hope students will come to learn and our openness to the unexpected and unplanned is what makes inquiry teaching so intriguing and satisfying. A question rather than statement can help us stay in that lovely, intriguing space – and doesn’t make us any less intentional.

How do you share or construct intentions with your students?

Just wondering…..