When I first became fascinated in inquiry-based approaches (too many years ago to say!), the focus for many of my conversations and indeed, my early research, was on how to plan. Back then, learning about inquiry helped me shift my thinking from planning thematically – or even in a more genuinely integrated way, to planning with a learning process in mind. Understanding inquiry helped me think more carefully about learning. Planning was no longer focused on making clever curriculum connections – it was about designing a process that would scaffold thinking from the known to the unknown, from shallow to deep and that would place the learner at the heart of all we did. My planning got better – much better. That approach to planning is now deeply embedded in my way of being as a teacher. It is organic and fluid. I don’t need to have it all mapped out the way I once did – I can combine my understanding of process with the immediate interests and needs of the learners with whom I work.

This emergent approach to planning is central to the inquiry teacher’s repertoire and remains a significant part of the work I do…but over the last few years in particular, I find myself thinking so much more about what happens when this plan gets put into action. The planning and the teaching are certainly deeply connected but - too often, inquiry seems almost synonymous with ‘units’. The cringe-worthy phrase “we do inquiry” usually means: we fill in an inquiry planner using a cycle/framework of inquiry – we document tasks in the boxes (even in an emergent way) and the tasks are student-centred - such as visible thinking routines, etc.

However well a ‘planner’ reads – what really counts is what the teacher actually DOES with those plans. If we simply list strategies or resources or the ubiquitous “discuss with children….” –have we thought sufficiently about how we will teach? I have experienced, many times, teachers emerge from the same planning meetings, with the same broad intentions and indeed with some excellent, promising learning engagements…. only to see true inquiry unfold in one classroom and not another.

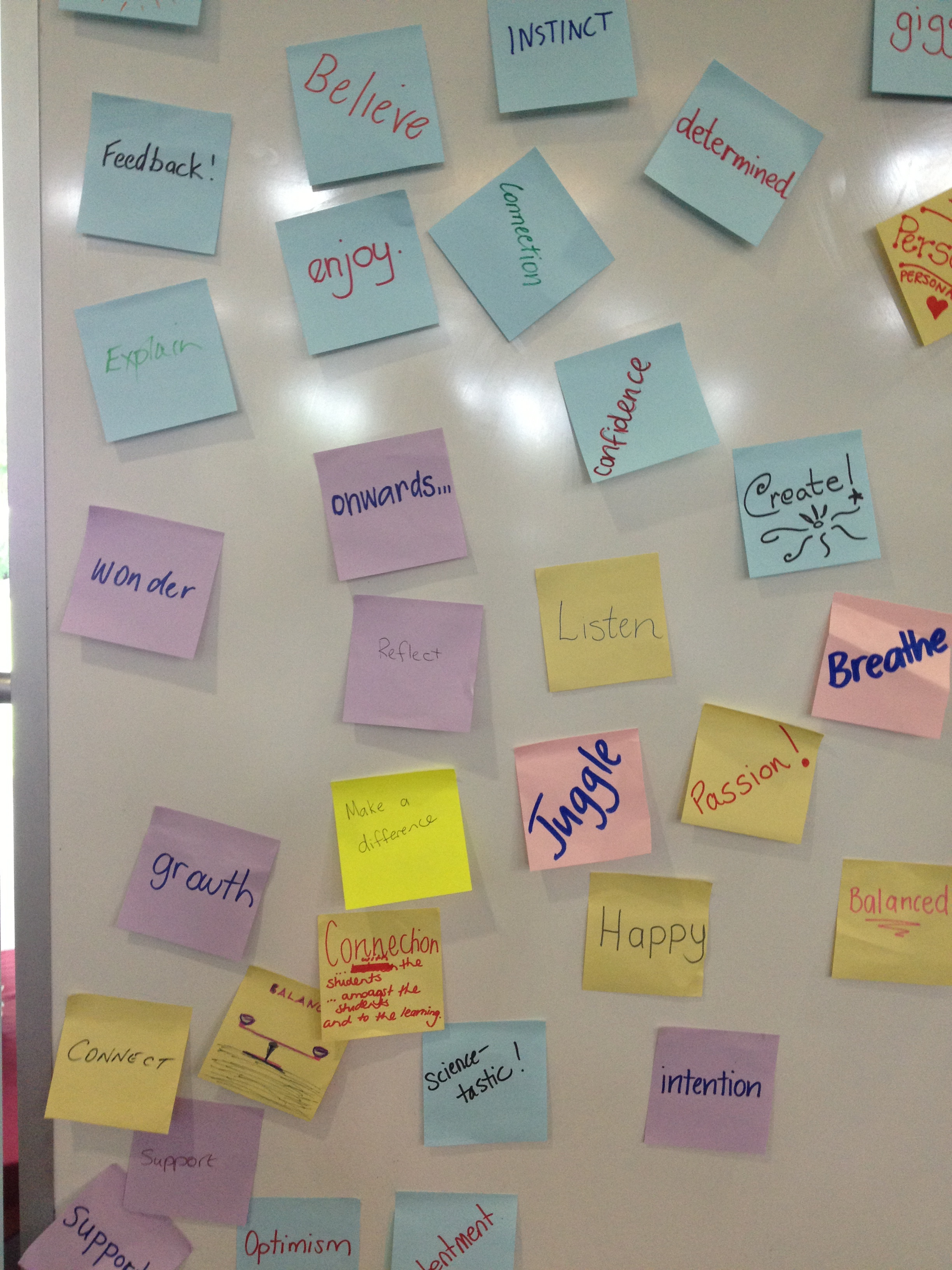

Inquiry is not just about knowing how to plan – it’s about how we teach. It’s about what we say to kids and how we say it. It’s about the way we listen and the way we feel about what our kids are saying. It’s about knowing when to step back and when to step in. The language we use and the silences we deliberately leave. It’s about what we are thinking about what we are doing. To one teacher “See, Think, Wonder” is an engaging learning task to be completed at the beginning of a unit – to another it is a window onto children’s theories, an opportunity explore how a student ‘sees’ a concept. A ‘unit of inquiry’ is not worth the paper it is written on if we don’t know what it means to be an inquiry teacher.

I have long been utterly intrigued by the question “what makes an inquiry teacher’ – why is it that some find it such a natural disposition and while others struggle SO much with sharing power or seeing a bigger picture? But I’ll save my musings on that for another time…. Today, I am thinking about what inquiry means for the act of ‘teaching’ itself. Here are techniques or approaches I observe inquiry teachers use. A dozen of the best…..

1. They talk less. It’s that simple (I’m still working on that one myself!!)

2. They ask more. The discourse in an inquiry classroom is rich with quality questions – inquiry teachers know how to use questions to help students uncover their own thinking and understanding.

3. They relate – with the heart as well as the head. The BEST inquiry teachers I see genuinely enjoy their students and know them. Knowing your students is the key to successful facilitation – particularly of personal inquiries.

4. They let kids in on the secret – inquiry teachers have a transparent style. It’s not just about putting learning intentions up on the wall – they constantly ensure their kids know why they are doing what they are doing. Inquiry teachers often think aloud – they reveal the complexities and the joys of learning to their students by being a learner.

5. They use language that is invitational and acknowledges the elasticity of ideas. Words like ‘might’ ‘could’ ‘possibly’ ‘wonder’ ‘maybe’ ‘we’ are used far more than ‘must’ ‘is’ ‘will’ ‘I’. They remain open to possibility…. and you can hear it in their voice. Inquiry teachers speak what Claxton calls “learnish” - and they help their students speak it too.

6. They check in with their kids – a lot. The teaching itself looks, sounds and feels like an act of inquiry. They listen, observe and ‘work the space’. They do not spend most of their time at the front of the room. The teach beside – sometimes ‘on the side’ and not – for the most part – on the stage.

7. They collaborate with their students. They trust them! The ‘asymmetry’ of power in the traditional classroom is challenged by inquiry teachers – they allow role reversal and are comfortable letting the learner lead.

8. They use great, challenging, authentic resources – not just the ones that are easy and on hand. They are hunters and gatherers – looking for objects, people, places, texts that will bring the world to their kids.

9. They are passionate and energetic. And that includes some of the most calm and quiet teachers I have ever worked with! I think that’s true of all the best teachers – inquiry based or not - but these teachers are passionate about investigation, about the thrill of discovery, about seeing patterns and the learner ‘getting it’ – they are genuinely interested in the world and relentlessly curious. And it shows.

10. They see the bigger picture – they have a good grasp of the significant concepts and skills relevant to the focus of students’ inquiry. They may not know all the facts – but they DO have a ‘birds eye’, conceptual view that is invaluable in scaffolding learning for children. You can hear it in the way they question.

11. They invite, celebrate and USE questions, wonderings, uncertainties and tensions that arise from their students. They may not be the questions they expected – but they use those questions to scaffold learning.

12. Traditional pedagogy sees the teacher provide a set of instructions, make sure everyone ‘knows what to do’, explain everything and THEN students might be given some time to do a task themselves. It’s about 80% teacher led and 20% student. Inquiry-based pedagogy gets kids doing, thinking and investigating – and the explicit teaching happens in response to what the teacher sees and hears. The 80:20 ration is reversed. Good inquiry teachers know how to get more kids thinking more deeply more of the time.

In inquiry schools, we spend a lot of time planning and documenting. These conversations are invaluable and I am not for a moment, suggesting this is not important. But let’s remember that what counts the most, as Hattie and others remind us, is what we think, do and say when we engage with our students. Programs and planners don’t make inquiry happen. Teachers and learners do.

What do you think it means to be an inquiry teacher?

Just wondering….