I was reading an interesting post from @langwitches in which she refers to @brholland’s slideshow from a recent ASCD conference. In true domino style, Beth's post got Sylvia thinking and blogging and Sylivia’s post got me thinking and blogging! The issue being explored by these two educators was around what we are ‘looking for’ when we walk into a learning space/classroom. Beth raised a number of key questions that we can ask to help reflect more closely on the effective use of technologies. The post and slideshow are great…as is Sylvia’s sketched response to it. You can find them here: http://langwitches.org/blog/2015/04/09/used-effectively-or-simply-used/ As readers of this blog know, I pretty much obsess over all things inquiry. So of course, this got me thinking about the questions that roll around in my head when I enter a classroom. Most of the time, I am looking through an inquiry lens … looking for connections between what I see (and hear) going on and inquiry learning/ teaching. I am lucky. I get to walk into many, many different classrooms in many different places and I am often intrigued by the things that signal 'inquiry' to me and, equally, by the things that, well...don't. So I am wondering: what questions do I ask?

Read MoreSeeing beyond the cupcakes – what ‘itime’ should really be about.

As many readers of this blog will know, I have a particular interest in how we can best provide opportunities for children to inquire into the things that matter to THEM as well as the things that we might bring to them. I strongly believe in the value of what we might call ‘shared inquiry’ but I acknowledge its restrictions in a context that allows a much more diversified and differentiated approach. In several of my partner schools, staff have worked hard to develop approaches to ‘personalised inquiry’ alongside more teacher initiated, shared inquiries. The work has been fascinating, complex, problematic and revealing - but the children tell us over and over again that they adore the chance to spread their wings, to investigate what intrigues them, to have more of a voice and to step outside the predictable content that dominates most of their school days. There is something deeply satisfying about walking into a learning space where some children are busily modifying recipes and preparing to cook, some are continuing with myth-busting style experiments, some are outside in the garden, some researching the relative fuel efficiency of various cars, some setting up an interview with a local author and another devising a digital survey to gather data about health and well being. The classroom becomes a microcosm of the world simultaneously explored by painters, scientists, sociologists, historians, geographers, activists, writers, musicians, engineers, chefs, naturalists …. I could go on!

Read MoreSowing the seeds for a great year of inquiry: 10 tips for term 1.

The school year has just begun here in Australia. It’s a time of great anticipation, resolution and excitement – I love the sense of possibility that accompanies this time. For many of us – having had a break – it is also a time of adjustment. In a sense, we return to our ‘teacher selves’ and with that, is an opportunity to think about that identity: how DO we see ourselves as teachers and how does this impact on the way we teach? I remember hearing Ken Robinson (in a lesser known talk) once describe teachers as gardeners. This is always a metaphor that has appealed to me. I like the nurturing connotation, the link to nature, the need to tend and care, the combination of planned and unexpected and, of course, the symbol of growth.

Read MoreSomething to talk about: Dialogic teaching – putting classroom talk at the centre of inquiry

I am delighted to share this guest post from a long time colleague of mine - Julie Hamston. Julie and I have written a number of books and articles together over the years and I continue to learn a great deal from our conversations about inquiry, teaching and learning. Julie's expertise is in the area of language - and, as you will see from this post, she is particularly fascinated in the role of talk in the inquiry classroom. I have previously posted some thoughts on the language we use with students and am in no doubt that one of the most important things we can do for learners is to strengthen our understanding of and skill in managing dialogue to support their' thinking. Talk is our central and perhaps most powerful 'tool of trade', as Peter Johnson reminds us: "Teachers' conversations with children help children build the bridges from action to consequence that develop their sense of agency" (Choice Words, 2004:30) I know you will find Julie's post thought provoking - I hope it gives you something to talk (and wonder!) about at your next team or staff meeting. Effective teachers of inquiry operate with a finely tuned set of strategies to encourage students to make their thinking visible and to share their understandings with others.

Although these strategies have sharpened our attention on the relationship between language and thinking, I suggest they are limited unless we better understand the way that classroom talk is intimately connected with student learning. Deep and meaningful inquiry is dependent upon the linguistic leverage teachers provide to students through language that is modelled, generated, recycled, consolidated and stretched within the context of inquiry. The explicit pedagogic language of the teacher, consciously focused on deepening and expanding the linguistic content of student responses, combined with strategies for exploratory and collaborative talk, helps students develop the discourse practices (such as predicting, reasoning, explaining, justifying, interpreting, problem solving) fundamental to inquiry.

This view is not a new one. Classroom-based researchers from all over the world have demonstrated through close analysis of teacher-student talk and student-student talk that the quality of linguistic interaction and feedback in the classroom impacts on the quality of learning. That said, I strongly believe that more time and patience needs to be devoted to authentic dialogic interaction in inquiry classrooms and that teachers make a stronger investment in the language both they and the students produce.

This dialogic approach to teaching involves two integrated foci on language:

- the language-specific routines that teachers draw upon within any inquiry focus: questioning; prompting; eliciting and cuing student responses; ‘pressing’ for more clearly articulated detail, information or explanation; repeating, reformulating and elaborating on student responses; and recapping what has been learnt.

- the collective, purposeful, and reciprocal language exchanged between students and between students and the teacher.

When we think of inquiry-based learning and the emphasis placed on shared work, problem solving, making connections and thinking through complex issues, the importance of dialogic teaching is clear. Neil Mercer and others view talk as helping students do the hard work of learning. Dialogic inquiry involves students in seriously working with the ideas of others, considering and challenging evidence, worldviews and perspectives, and reaching logical conclusions.

My recent work on dialogic teaching

Throughout 2014, I have been working with the Principal and staff of Meadows Primary School in Victoria, Australia to establish a whole school commitment to dialogic teaching, initially around inquiry-based learning. The student demographics at this school are shaped by generational poverty; household and neighbourhood disadvantage due to chronic unemployment and a high proportion of sole parents; significant ethnic diversity in the community, including Indigenous Australians and new and settled migrants for whom majority English is an additional language; as well as widespread first language ‘impoverishment.’

We were interested in the quality of teacher and student talk in the classroom. We wanted to see, more clearly, the ways in which teachers used language to scaffold thinking and learning, to build, deepen and extend their students’ language repertoire so they could make their reasoning ‘visible.’ I designed a program that combined professional learning on dialogic approaches in the classroom, analysis of classroom transcripts and videos, classroom observations, feedback and evaluation.

Teachers were also required to collect data of their own talk interactions with students and to analyse these in terms of the language techniques they were using (for example, did they reformulate students’ responses? Did they put a ‘press’ on students’ language? Did they cue students into possible answers?). In addition, they were encouraged to introduce exploratory talk techniques to their students (the Thinking Together project coordinated by Mercer and colleagues at the University of Cambridge formed the basis of this task https://thinkingtogether.educ.cam.ac.uk).

Teacher volunteers were then invited to be involved in a pilot project involving the trial of dialogic approaches within the context of inquiry-based units of work. Two year levels responded: the Foundation Year (consisting of four teachers, led my me) and Years 3 and 4 (consisting of four teachers and facilitated by the school’s lead teacher, Adam).

From: Tayla Cosaitis’ Year 3/4 class: Ground Rules for Talk.

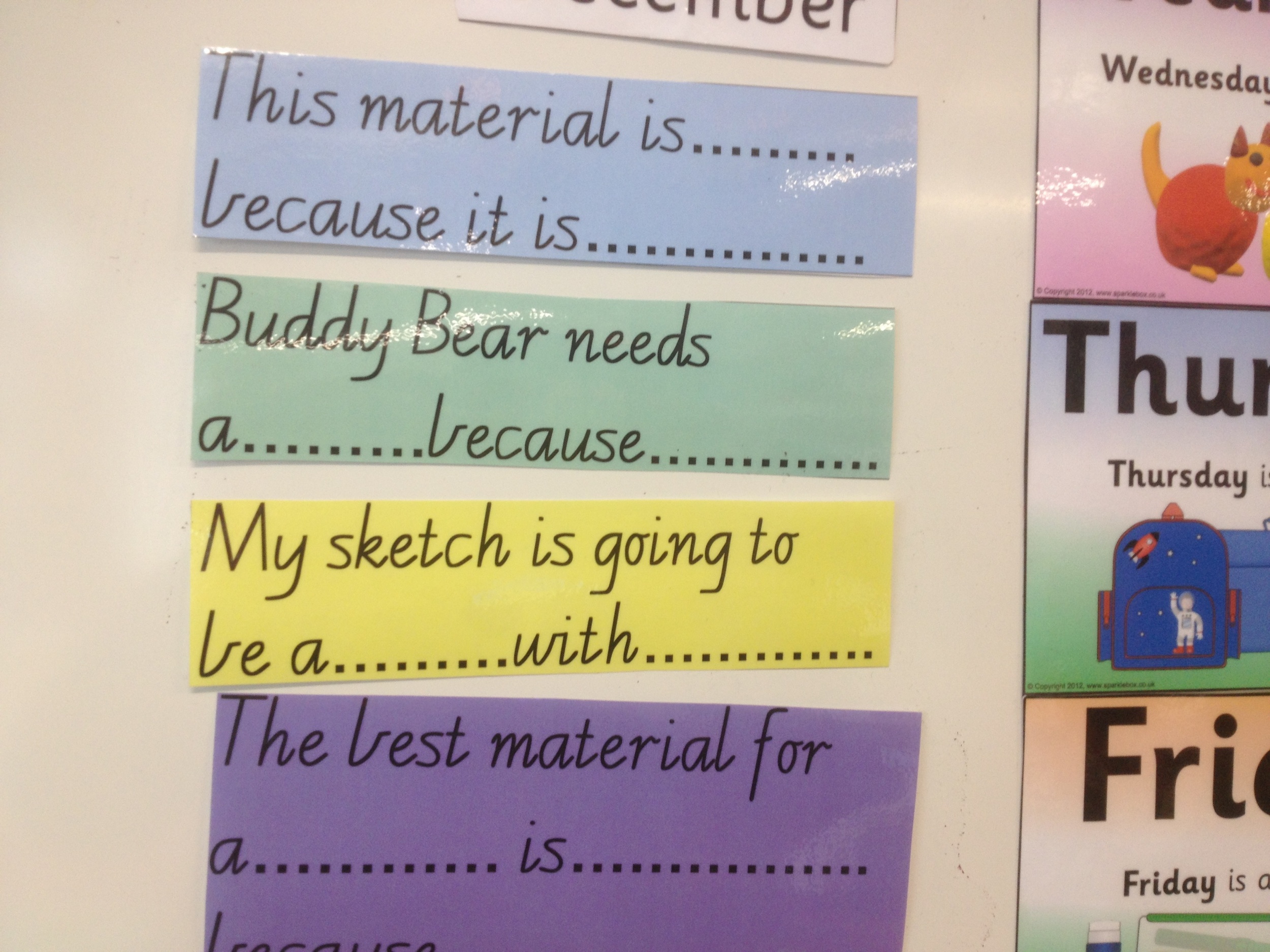

The Foundation teachers, working with 5 year olds (Sarah Lynch; Laura Di Lizia; Stephanie Webster and Libby Morris) collaborated closely with me on building students’ capacity to share their thinking, using longer stretches of language incorporating reasoning words such as ‘because’ and ‘if.’ In consultation with the research literature, we designed language frames relevant to their students’ inquiries (“ I like your idea because…” ; “ I will build a …. because….”; “I will use… because….”).

From: Laura Di Lizia’s Foundation class: Design, Creativity and Technology Unit – Building a House for Buddy Bear.

The teachers also ‘planned in’ their own and student language to their inquiry units, established ‘talk buddies’ for an initial foray into exploratory talk, and introduced students to the ground rules for active listening, talking and sharing with others.

The analysis of transcripts was central to the teachers’ professional learning. Examples such as this one were used to identify (i) the language repertoires used by each teacher and (ii) any growth in the students’ linguistic reasoning:

Teacher: Sofia, can you tell me what you have used to make your couch? (Eliciting a response)

Sofia: I have used material. We used cotton balls and we got the Buddy Bears to test them out on them… and we used cardboard and we used bubble wrap.

Teacher: Great. You used lots of things. Can you tell me why? (Request for student to provide a reason). So can you say “I used cardboard and bubble wrap and material because… (Providing a language frame as support).

Sofia: Bubble wrap.

Teacher: Put it in a full sentence. “I used …” (Putting a ‘press’ on the student’s language in the hope for a more comprehensive and reasoned response).

Sofia: We used materials because to make it comfy (sic). We used cotton balls to make it even more comfortable. We used cardboard to make it strong. We used bubble wrap to make it soft. We used glue to glue it together (Putting language and thinking together).

The explicit apprenticeship of students into the discourse practices of inquiry has been so positive that teachers report a shift in students’ capacity to use talk to provide evidence and justification, and to think through alternatives. Importantly, the teachers say they are more focused on their own language use. Great examples of this from the teachers in Foundation year include:

- Reformulation of student responses (Did you mean…?)

- Direct elicitations – (“Can somebody …? Who knows…?: “I want to know what you know about sketching.”)

- Exhortations (“Who is thinking the same/different?”)

- Repeating student responses to consolidate learning (“Well that’s a lot of information there. I’m going to break it down for everyone. Shreya said …. Shreya went on….. and explained more………………….)

- Recaps to consolidate understanding (“OK, so we have used our observation frames to look at the weather…”)

- Connecting feedback to inquiry (“Great thinking!; “I love the connection you just made.”)

- Building on student responses (“I just want to bring it back to what Louie was saying.”)

- Requests for reasoning (“You have to tell me why. Remember to make a prediction and tell me your reason.”)

- Putting a ‘press’ on student language (“Can you put your answer in a full sentence?”; “Can you begin by saying ‘I think…”; “Remember our language frames: “I predict…because…”)

Work continues on dialogic teaching at Meadows Primary School in 2015 and 2016 – watch this space?

Contact

Dr Julie Hamston is an education consultant and a Senior Fellow in the Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne, Australia. She can be contacted by email at: j.hamston@unimelb.edu.au

If you are interested…

Alexander, R. Dialogic teaching. Retrieved from http://www.robinalexander.org.uk/dialogic-teaching/

Dawes, L. (2008). (Chapter 2 ‘Talking Points’) The Essential Speaking and Listening: Talk for learning at Key Stage 2. Retrieved from https://thinkingtogether.educ.cam.ac.uk/resources/About_Talking_Points.pdf

Hamston, J. (2006). Bakhtin’s theory of dialogue: a construct for pedagogy, methodology and analysis. The Australian Educational Researcher, 33, 1, 55-74.

Haneda, M. W., G. (2010). Learning science through dialogic inquiry: Is it beneficial for English-as- additional-language students? International Journal of Educational Research, 49, 10-21.

Haneda, M. W., G. (2008). Learning an additional language through dialogic inquiry. Language and Education, 22, 2, 114-136.

Mercer, N. (2008). Talk and the Development of Reasoning and Understanding. Human Development, 51, 90-100.

Mercer, N. D., L. (2010). Making the most of talk: Dialogue in the classroom. EnglishDramaMedia, 19-25.

Taggart, G., Ridley, K., Rudd, P. & Benefield, P. (2005). Thinking Skills in the Early Years: A literature review. Retrieved from http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/73999/1/Thinking_skills_in_early_years.pdf

Zhang, J. D. S., K.A. Collaborative reasoning: Language-rich discussions for English learners. The Reading Teacher, 65, 4, 257-260.

Seeing things anew: being a tourist in our own classroom

The more often we see the things around us - even the beautiful and wonderful things - the more they become invisible to us. That is why we often take for granted the beauty of this world: the flowers, the trees, the birds, the clouds - even those we love. Because we see things so often, we see them less and less. Joseph B. Wirthlin

This is a more personal, reflective post than I usually write on this blog…but hey, blogging should be a bit personal. Right? So here goes…

Over the last six weeks or so, I have spent a lot of time working and living away from home. For some of that time I have been fortunate to have my family with me but, regardless, my work has taken me to extraordinary places far and wide. It’s been a while since I have had the full weekend at home so, this evening - after beautiful, warm, blue pre-summer Melbourne day – I took myself out into my back garden of over 20 years and I…looked up and out. I noticed our native frangipani in full bloom, I watched our golden retriever get teased by our bossy chooks and I listened to the delicious, summery call of the rainbow lorikeets as they flew overhead. I watched dusk settle over my suburban back garden, poured a second cup of tea and felt – gratitude.

Many international readers of this blog know all too well what it feels like to see your home in a new light and to experience the gift of appreciation that comes when you spend time away from a place so familiar to you it has become somewhat invisible and unnoticed. I left full-time classroom teaching years ago - when I moved into teacher education and then into consulting. I have never stopped thinking of myself as a teacher (it’s what I always write in the section asking for ‘occupation’ on official forms), but I guess I spend more time ‘teaching teachers’ nowadays. Same, same – but different. Working with children – and being in a primary school classroom is my natural habitat but one that I often leave for extended periods. Over the last 12 months, however, I have found myself working more and more alongside teachers and children in their classrooms as part of our own inquiries into what it means to be ‘an inquiry teacher’. I have always with children as part of my PL approach - but the preparedness of teachers to invite me in to their classsrooms and for us to work together has definitely grown over time.

Many international readers of this blog know all too well what it feels like to see your home in a new light and to experience the gift of appreciation that comes when you spend time away from a place so familiar to you it has become somewhat invisible and unnoticed. I left full-time classroom teaching years ago - when I moved into teacher education and then into consulting. I have never stopped thinking of myself as a teacher (it’s what I always write in the section asking for ‘occupation’ on official forms), but I guess I spend more time ‘teaching teachers’ nowadays. Same, same – but different. Working with children – and being in a primary school classroom is my natural habitat but one that I often leave for extended periods. Over the last 12 months, however, I have found myself working more and more alongside teachers and children in their classrooms as part of our own inquiries into what it means to be ‘an inquiry teacher’. I have always with children as part of my PL approach - but the preparedness of teachers to invite me in to their classsrooms and for us to work together has definitely grown over time.

This past week alone, I have participated in a five year old’s elaborate personal inquiry into how to be a ‘café worker’; listened in awe as ten year olds shared their theories of light and shadow with me as we inquired into science; figured out –with the help of some 7 year olds – how life in rural Victoria might be the same and different to life in the city at the same time as investigating the skills of researching through video; inquired into the thinking skills of summarising, comparing and contrasting with 6 year olds; watched as another group of 6 year olds organised questions into google-able and ‘better to ask someone’ questions….I could go on. It’s been a big week of teaching and learning with children and their teachers – I feel deliriously drenched in inquiry!!

So – what’s all of that got to do with the lorikeets in my back yard?

When I am given the great privilege to work with teachers and their children – I get, in part, to return to what I regard as my ‘natural habitat’ – the classroom. And see it anew. I experience the kind of perspective afforded to the traveller returning home. I notice the things that we can all, so easily take for granted. So at the risk of sounding a bit ‘cheesy’, I want to acknowledge what it is I have been noticing and savouring about this privileged, sacred job we do as teachers:

- That, for the most part, children are a joy to be with. When we open OUR hearts to them – they return that connection in spades.

- That participating in the growth of a child’s understanding, seeing an idea take flight, seeing a child ‘get it’ is SUCH a privilege and so exciting. Sometimes I can’t believe I get to witness that!

- Teaching is without doubt one of the most fascinating, intriguing jobs one can have. Sure – you can make it tedious by choosing to do the same thing year in, year out but as an inquiry teacher you never know what the day – even the lesson – will bring. There are not many jobs I can think of that afford you that kind of creative experience.

- That teaching is FUN. Few lessons go by for me where I have not cause to smile or share a genuine laugh with children - the positive energy that a good lesson can bring to your own wellbeing cannot be taken for granted

- That teaching means learning. Lately, I have been asking kids to remember to ask me ‘Kath – what did you learn today?’ at the end of my time with them. They always remember. And I love that moment. I never struggle to think of something I have learned or now understand a little more deeply. What other job allows you to regularly discover and re-discover so much about the way the world works across such a broad pallet of disciplines?

This is merely a small sample of the many gifts that teaching brings. Gifts that can so easily become unseen – inevitably masked by familiarity. Opportunities to see our work anew are vital – for maintaining perspective, positivity and a growth mindset.

It’s not just me that benefits from seeing and feeling my work in a fresh light whenever I return to a classroom. I have lost track of the number of teachers who have said to me things like: “I just loved being able to watch and listen to my kids from a new perspective – I am seeing them differently and noticing things I fail to noticed when I am teaching.” Even teachers who routinely share a classroom space (team teaching/flexible learning spaces) often reflect on the missed opportunities they have to more closely observe their students.

Of course, I am well aware that the work I do sits in a very different context to that of someone in the same environment day in day out – my focus is purely on that moment of teaching and learning for the children and teachers in that space. I am not thinking about the meeting with a difficult parent after school, the reports I have to start writing or the meeting I have to prepare for! I acknowledge the rarefied opportunity I am given – but I think it is one we can seek to replicate more often in our day to day work as classroom teachers. This can happen by teaching eachother’s classes, visiting other schools or spending time in specialist classes to watch our students from a different vantage point or simply by giving ourselves permission to slow down and reflect.

The best inquiry teachers I know are those who have a strong, inquiring disposition themselves. They approach their teaching with curiosity and wonder. They see themselves as learners and assume that the day will bring THEM new discoveries as well as their students. Inquiry is so often about seeing something anew – experiencing fresh thinking, fresh perspectives, evolving skills – a continuous process of ‘becoming.’

When we see something often, the danger is, we see it less. Perhaps we need to be occasional tourists in our own classrooms, or momentary strangers in our own schools – to remind us of what we have.

How do you foster a culture of gratitude and positivity in your staff/team/classroom?

How do you keep your own perspective fresh?

What helps you step back and notice?

Just wondering....

Passion and curiosity can’t happen ‘on demand’! or 'What do the 'shoulder shruggers' need?'

As many readers of this blog know, I have been busy exploring various approaches to personalized inquiry in schools. This has been one of my own significant ‘inquiries’ over the last few years. Providing more personalized inquiry opportunities for students is certainly gaining in popularity and momentum and happens in various ways through such approaches as genius hour, innovation days, itime, etc. Each year, I learn many new lessons about how to make these opportunities work more effectively to ensure high quality, rigorous learning while providing choice and flexibility. Two comments in recent times have given me pause for thought. The first came from a child - not from a school I have worked in - but one that is obviously making efforts to personalize learning. The children have all been given the opportunity to do a ‘passion project’. They have 4 weeks and are using some class time and some homework time to complete it. They have simply been told to ‘investigate their passion’ To be fair, the school does not seem to have a strong, explicit inquiry program so she may well felt more equipped and connected if it had. Regardless, it's not the first time I have heard a child say… “But I don't really HAVE a passion, I don’t know what to do!” Far from being excited by the prospect of investigating something of her choice, this 11 year old was floundering - grasping at random ‘topics’ her teacher had selected and shrugging at any suggestions I made related to some of her (admittedly limited) interests outside of school.

The second comment I heard was from a parent following a talk I gave recently where the focus was on ‘wandering and wondering’ with your child and the delight and power of young children’s questions. At the end of the talk she said her own child asked lots of questions and was a keen, curious learner at home…but when it came to “discovery time” at her son’s school, he was often ‘stuck’ and did not know what to do – he also felt rushed to pick something to work on for the session and expected to suddenly ‘switch on’ his curiosity. I sensed a few problems with the way these sessions may have been run but did not take that further. What I DID say was that like all learners, we can’t expect kids to be curious ‘on demand’ .

Passion, strong interest, curiosity, a desire to find out or learn to do something new or better….these are the driving dispositions of personalized inquiry. Some children almost spill over with enthusiasm and an eagerness to pursue something while others - well not so much. So, what do they need? What do the ‘shoulder-shruggers’, the ‘I dunno’s’, the “I’ll do what he’s doing” kids need ... in order to be more authentically engaged in experience of personalized inquiry?

- Time. Rather than seeing the foci for itime/genius hour as something to work on in dedicated sessions – encourage kids to build a bank of possibilities throughout the year. Researcher’s notebooks, wonderwalls, ideas boards, etc. allow the learner to collect their own questions and interests as they arise – rather than ‘on demand’. Gradually building a collection of possibilities gives the students something to ‘dip into’ when they have an opportunity to launch into a new journey of inquiry. Curiosity – even passion – as dispositions that need to be nurtured as part of a wider classroom culture.

- Inspiration. Part of the teacher’s role is to be ever on the look out for stimulating, interesting questions/issues/events that might pique interest and be worth pursuing…share these with the children and create a bank of wonders for those students who might need that extra support. Websites like www.wonderopolis.org are excellent resources. Ted talks, short video clips, articles - can all provide great springboards for interest. Teachers who consistently model their OWN enthusiasm for learning, finding things out and who show excitement about the range of things kids themselves are interested in go a long way to providing an inspiring atmosphere for inquiry. And while we encourage children to become passionate learners – let’s not shoot ourselves in the foot by making children feel that if they are not PASSIONATE about it, it's not worthy! A thoughtful, even reserved interest may be enough to provoke a quality investigation. Once underway, itime or its equivalent can generate its own energy as children gain ideas from each other. Have students share their investigations in small groups, conduct gallery walks, keep public lists and charts of the ideas they have explored – peers inspiring peers.

- Breadth. Beware the dreaded ‘topic’… itime investigations do not have to involve students inquiring into a random topic (eg: panda bears, formula 1 racing) …they certainly may…but they may also be an opportunity to improve a skill or learn a new skill, to work on an action plan, to canvas people’s opinions about an important issue, to create make and build. If students think of a ‘project’ the way many of their parents experienced a ‘project’ it is no wonder they can’t get past simply choosing a topic. The best personalized inquiries are also seen by students and teachers as an opportunity to ‘build their learning muscle’ - it’s so much more than the content.

- Forethought. Many of the more successful personalised inquiry programs I see, really scaffold students thinking before, during and after their investigations. Students complete proposals (careful not to make them too arduous!), or keep researcher’s notebooks, and conference with peers and teachers to gain support and advice rather than simply ‘coming up with a topic’.

- Trust: One of the struggles we have as teachers is our own tendency to judge the choices that children make. We give them a choice – but we can also make it pretty clear when we disapprove of the choice! Perhaps this is why some are tentative to say what they want to explore. Of course there will be some things that won't be appropriate for investigation – and criteria for that can be worked out with the class. But we need to be mindful not to shoot down their interests because we might not judge it worthy of spending time on. The best teachers I see know how to take that child's desire to learn about (eg soccer) and help them develop a question or a focus for investigation that stretches thinking without devaluing their interest (eg: How has the game of soccer changed in the last 50 years – is it a better game now than it was?Why?). Spending time in thoughtful conversation with children who need that extra support is vital. Just as we conference with students about their reading and writing – so too should we about their researching. This is not ‘teacher free’ learning!

Providing opportunities for true, personalized inquiry as part of our classroom program can be a wonderful way to support the growth of the learner. But if we expect them to ‘turn on the curiosity’ for one session a week without a broader culture of inquiry and the necessary time for reflection and inspiration, well…I guess we can expect our fair share of ‘cut and paste’ posters and half-hearted powerpoint presentations.

How do you encourage and sustain authentic passion and curiosity in your classroom?

Just wondering…